All Topics

- Alchemizing Music Concepts for Students

- Artist Spotlight

- artium gift card

- Artium Maestros

- Artium News

- buying guide

- Carnatic Music

- Devotional Music

- Editorials by Ananth Vaidyanathan

- Film Music

- Guitar

- Hindustani Classical Music

- Indian Classical Music

- Indian Folk Music

- Insights

- Instruments

- Karaoke Singing

- Keyboard

- Kids Music

- maestros

- Music Education

- Music for Kids

- Music Industry

- Music Instruments

- Music Legends

- Music Theory

- Music Therapy

- Piano

- piano guide

- Success Stories

- Tamil Film Music

- Telugu Film Music

- Time Theory

- Tools

- Uncategorized

- Vocal Singing

- Vocals

- western classical music

- western music

- Western vocal music

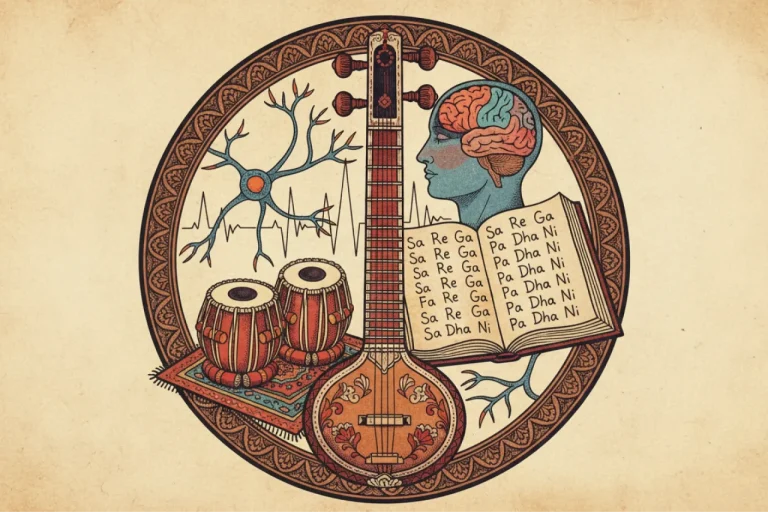

The Lifeline of Hindustani Classical Music: Improvisation In Music

The Lifeline of Hindustani Classical Music: Improvisation In Music

Table of Contents

Why Hindustani Classical Music Feels Difficult at First?

The typical reaction from almost all music lovers is that Hindustani Classical Music is not easy to understand when they first start listening to it. And yes, that’s a fact — one that surprises and even frustrates many first-time listeners. Let us try to understand the problem first. Why is it complicated to grasp? Why doesn’t it immediately sound “enjoyable” like a catchy film song or a popular tune on your playlist? Why don’t we start grooving to it the moment we press play on our favorite sound systems?

The answer lies in the nature of this music itself. Improvisation in Hindustani Classical Music is deeper than what we think or assume; it demands attention, patience, and, most importantly, a willingness to listen deeply. It’s a slow unfolding of emotion, mood, and thought, unlike most modern music that is designed for instant appeal. Another point is that Hindustani Classical Music typically doesn’t incorporate electronic music or studio effects. But once you get past the unfamiliarity, a whole new world begins to open up.

The Familiar Idea of Music Vs the Concept of Hindustani Classical

The known concept of music is this: there will be some lines, or some verses, a composed tune for those lines, and the musical pieces playing in the beginning (Prelude), and between two verses (interlude). This entire production can be considered a ‘song’. When it comes to Hindustani Classical music, the entire concept is something distinct, and that difference is not easily comprehensible to many.

This same difference causes the initial reluctance when we start listening to Hindustani Classical music. The first part of the difference lies in the name itself; when someone presents a ‘song’, they are presenting a composed piece of literature.

But when someone is going to perform Classical, he/she is going to perform a Raag, and under the umbrella of the Raag comes a composition, called a ‘Bandish’. This difference is taught by a Guru when we start learning Hindustani Classical.

Two Important Terms: Nivaddha & Anivaddha

Let’s try to break down this difference a little more. First, we need to know two Indian terms: NIVADDHA and ANIVADDHA. ‘Nivaddha’ means something which is already composed, like a composition of some verses, like a song. ‘Anivaddha’ is something that can be done in addition to the ‘Nivaddha’ part. That simply means, ‘Anivaddha’ is IMPROVISATION.

There are portions of both Nivaddha and Anivaddha in every genre of Indian Music, but in Hindustani Classical, the allotment of these two portions differs. In any other Music, the Sur or composition of the verses can be revised with some improvisation, the musical pieces can be improvised while performing, but after all of these, the percentage can roughly get to this:

Nivaddha: 80%

Anivaddha (If any): 20%

Here is the twist. In Hindustani Classical, THIS percentage becomes:

Nivaddha: 25% (Just the Bandish, a small, composed piece of poetry)

Anivaddha: 75%

This means that Hindustani Classical is more dependent on thinking and creating something on the spot. The artist is not just rendering a script or reciting a piece of poetry; they are sculpting something immersive, right before your eyes.

Like here, Pandit Venkatesh Kumar Jee sings Bandish in Raag Durga, but his singing becomes more of his thoughts and creativity, transcending the composed Bandish:

A Gentle Note for New Listeners

Here is a simple piece of advice for listeners and music lovers, before we delve into the world of Improvisation.

Have some patience, there’s no rush to understand all of these things right from the beginning. The impatience and irritation happens due to a frustration that “I am not understanding anything!” Relax, you DON’T really need to understand everything in one go. Start by just trying to absorb the calmness and tranquility of the music! Enjoy the slow melody, imagine that something abstract is being unfolded. The idea about the richness comes later. The more you listen, the more you get into this. That’s it!

The World of Improvisation: Key Elements

Now, let us take a trip to this world of Improvisation from a Learner’s perspective.

This major part of Anivaddha consists of several significant elements: Aalaap, Vistaar, Bol Banaav/Bol Banaavat & Taan (Sargam Taan, Aakaar Taan, Bol Taan).

Now we’ll try to get an idea of each of these elements based on these key points,

- What are these?

- How are these performed?

- How are these learnt?

What are These, and How are They Performed?

- Aalaap: The Invocation of the Raag

Also known as ‘Swar Vistaar’ / ‘Avchaar’ in various styles / gharanas; the element ‘Aalaap’ comes from the ancient form of Hindustani Classical Music, Dhrupad. This is basically introducing the Raag or the melodic framework to the audience. It’s almost like you are a priest who’s just about to start the rituals of worshipping the deity.

You start with the Raag phrases, gradually unfolding it more. When you culminate, an ambiance of the Raag is built; everyone can feel that. After you finish singing the Aalaap or this introduction part, you start with the composed piece, the Bandish. Here you sing the composition with the Bhaav (feeling/emotion) of that Raag and that particular poetry. There are usually two parts/verses of a Bandish, the first verse, Sthaayi and the second verse, Antara. After starting with the Sthaayi, another door opens, Vistaar….

- Vistaar: Expanding the Raag

Also known as ‘Alaapchaari’ in some styles / gharanas, Vistaar, as the name suggests, simply means exploring the Raag more, demonstrating more possible ways of the Raag with an adherence to the emotions of the Bandish but this time, it is done in and honouring the Taal-cycle or avartan. One added note is that Vistaar can be a great thing to see the space between two beats of the taal.

Vistaars are usually done with Sargam, Aakaar or using the Bandish bols (the most popular form). You sing some vistaars based on the Sthaayi and then you move to Antara, and you sing some vistaars based on the Antara. The usual rule is, vistaars on Sthaayi deal more with middle to lower octave and vistaars on Antara deal more with middle to higher octave. After singing vistaars on Antara, you come back to the Sthaayi, only to start some rhythmic action, called Bol Banaav / Bol Banaavat!

- Bol Banaav: Expressive Wordplay Within Rhythm

Here you use the bandish bols / words in some meaningful fragments to sing this part. The name ‘Bol Banaav or Bol Banaao or Bol Banaavat’ suggests very clearly, “jo Bol diye gaye hain usme se lekar apna ‘bol banao’, apna interpretation do!” (‘Create something of your own from the given words.’)

Here, you sing some improvised pieces of the bandish rhythmically, maintaining the taal cycle. When you are done with these, you are ready for the next step: The world of Taan!

- Taan: Rivers of Rhythm and Melody

THIS part of Hindustani Classical Music is very crucial as this part is the toughest part to sing, to learn, and even to understand. Understanding this is a challenge in the first place and that is why many people who might be lovers of other genres of music have misinterpreted this thing in different manners; sometimes in unpleasant ones!

One easy-to-digest idea can be this: imagine rain, streams, and waterfalls and mix these three in your imagination; now replace the water with notes! Yes, that can be a basic idea of Taan! This is purely a rhythmic action with notes, beats, and the spaces between beats; melody and timing both play vital roles here. Taan is sung sometimes with clear articulation of notes i.e., ‘Sa Re Ga Ma’, that’s called Sargam Taan; sometimes Aakaar or open ‘Aaa’ Vowel, that’s called Aakaar Taan, and sometimes with the Bandish Bols / phrases of words, that’s called Bol Taan. And gradually the performance comes to an end.

The Three ‘Roop’s (Forms) of a Raag when it’s sung

As far as I have learnt and realized, a performance of a Raag in Hindustani Classical Music has three significant layers. We can see this in a different way that any Raag, when performed, has three forms or Roop(s):

- Naad Roop (The sound of the Raag; Aalaap)

- Bhaav Roop (The feeling or emotion of the Raag; Bandish & Vistaar)

- Chhand Roop (The rhythmic expression of the Raag, Bol Banaav & Taan)

Insights Into the Learning Process

The ‘Nivaddha’ Part of the Bandish can be learnt in the first class only if you are musically a little strong. The capability of absorbing or copying a melodic structure just by listening can help here to learn the bandish.

The difficulty starts with the ‘Anivaddha’ part. When learning Aalaap, Vistaar or Taans, we try and we fail again and again. But that is how it is learnt. Ideally, we should learn to develop our imagination and our creativity from day one; this is what I feel but in most of cases this doesn’t happen.

In most training systems, learners are given a composed set of Alaap, Vistaar, and Taan, which is a good starting point. However, in most cases, learners stick to these memorized sets only, which does not lead them into the world of imagination. The prominent form of Hindustani Classical music is known as Khayal, which means ‘imagination.’

The Four Pillars of Learning Hindustani Classical Music

A learner can depend on four pillars to learn and master these things:

- Learning under the tutelage of a Guru / Mentor

- Thinking and thinking on whatever is being learnt

- Practice: being okay with multiple failures during practice, as this is a part of the process!

- Listening and analyzing maestros’ performances. Attending Live concerts and spending time on YouTube!

And last but not least, questioning. Yes, this helps a lot in thinking and developing!

The Final Aspect: Spirituality

Beyond the technical brilliance, beyond the grammar of Raag and Taal, lies a deeper, quieter truth — Hindustani Classical Music is a spiritual journey. This realization comes after a certain period of listening or learning.

This music is not just a form of entertainment, but a path to introspection and transcendence. The great masters often didn’t perform to impress an audience — they sang to connect with the divine. Music was, and still is, a form of ‘Saadhana’ — a meditative journey.

Swami Vivekananda has beautifully said, “Music is the highest art and to those who understand, is the highest worship.”

The slow unfolding of a Raag, the stillness of an Aalaap, the emotional intensity of a Bandish, the flow of a Taan — all these elements gradually quiet the external noise and bring the listener and the performer closer to something sacred.

Even if we don’t “understand” every note or phrase, we often feel something shift inside — a kind of stillness, surrender, or emotional release. That is the spiritual power of this music.

Curious About Classical? You’re Already Halfway There

At Artium Academy, we believe that music is not just something you learn — it’s something you experience. Hindustani Classical Music, with all its depth and richness, is not reserved for a chosen few. It’s a living, breathing art form meant to be explored by anyone who feels curious, drawn, or even just quietly intrigued.

Whether you’re a complete beginner or someone rediscovering a forgotten love for classical music, Artium offers a guided path, led by accomplished Gurus, personalised learning, and an inspiring community. If this article stirred even a flicker of interest, that spark could be the beginning of something truly transformative!

FAQs on Lifeline of Hindustani Classical Music

Hindustani Classical Music is a rich art form that demands patience, attentive listening, and consistent practice. The depth and intricacies are challenging enough to understand or chase during the initial phase of listening or learning. It is based on centuries-old traditions and needs an understanding that goes beyond the notes. With dedication, one can gradually understand, learn, and sing it beautifully, expressing subtle emotions and connecting with listeners. This connection offers fulfillment and a cultural bond that feels unique once the learner truly engages with its essence.

Nivaddha refers to pieces that follow a fixed melody (Sur) rhythm cycle (Taal), which forms the structured backbone (Bandish) of a performance. Anivaddha occurs when the artist incorporates original and creative ideas (Aalaap-Vistaar-Taan) within the Nivaddha framework, adding personal expression and improvisation. Together, they create a beautiful journey that combines something fixed with something free-flowing.

‘Nivaddha’ has to be learnt directly from the Guru (teacher), while ‘Anivaddha’ (Improvisations) grows through Learning, Listening, Practicing, and Thinking. Anivaddha (Aalaap-Vistaar-Taan) shouldn’t be taught as Nivaddha, because memorization can replace imagination. One way to teach is to encourage learners to think and sing simple improvisations without judgment or fear of mistakes, understanding that making mistakes is a natural part of the learning process. Over time, improvisation becomes a natural extension!

Some common challenges include training the ear and having a good sense of hearing to identify and reproduce precise notes and microtones (shruti). Maintaining discipline in daily riyaaz (practice) despite a busy schedule. Understanding complex ideas (Thaat vs Raag), intricate details of delicate Raags (e.g., Todi, Bihaag, Bhimpalasi), and improvisational rules. Overcoming the initial unfamiliarity that can make the music feel difficult to grasp.

Yes — it’s traditionally seen as a path to self-awareness and emotional depth. Many Raags are designed to evoke specific moods, times of day, or spiritual states. Even in Ancient scriptures, specific Raags are found to be related to specific deities. For example, Raag Bhairav is often associated with the meditative state of Lord Shiva. Singing or listening mindfully can be a form of meditation. The Guru–Shishya tradition itself nurtures humility, devotion, and discipline.

Artium Academy offers guided learning with accomplished Gurus who make this age-old tradition approachable for modern learners. Its structured curriculum blends theory, practice, and creativity, ensuring a strong foundation. Students receive personalized feedback to progress at their own pace, while a vibrant learning community keeps them supported, inspired, and connected to the art form.