All Topics

- Alchemizing Music Concepts for Students

- Artist Spotlight

- artium gift card

- Artium Maestros

- Artium News

- buying guide

- Carnatic Music

- Devotional Music

- Editorials by Ananth Vaidyanathan

- Film Music

- Guitar

- Hindustani Classical Music

- Indian Classical Music

- Indian Folk Music

- Insights

- Instruments

- Karaoke Singing

- Keyboard

- Kids Music

- maestros

- Music Education

- Music for Kids

- Music Industry

- Music Instruments

- Music Legends

- Music Theory

- Music Therapy

- Piano

- piano guide

- Success Stories

- Tamil Film Music

- Telugu Film Music

- Time Theory

- Tools

- Uncategorized

- Vocal Singing

- Vocals

- western classical music

- western music

- Western vocal music

Understanding Tala In Music: The Time-Framework of Hindustani Classical Music

Understanding Tala In Music: The Time-Framework of Hindustani Classical Music

Table of Contents

The Beating Heart of Indian Classical Music….

From taking the first step to feeling the pulse of taal….

Close your eyes for a moment. Tap your fingers softly on the table. Maybe you started slow… maybe you rushed… but in that simple act, you’ve entered the sacred realm of Taal — the time-cycle that breathes life into Indian classical music.

In Hindustani music, we often speak of swar (melody) and raga as the soul. But if melody is the river that flows, taal is the riverbank — the rhythmic framework that gives it direction, pause, acceleration, and drama. Without it, music would float away, untethered. With it, music dances — poised, expressive, and deeply grounded.

From Chhand to Taal: A Journey Through Time

Before there was taal, there was chhand — the Sanskrit concept of meter or rhythmic arrangement. Ancient Vedic chants were recited with metrical precision, based on syllabic length and rhythm.

These were not musical compositions per se, but they laid the foundation of Indian rhythm. Over centuries, these metrical patterns evolved into theka — a structured arrangement of rhythmic syllables (or bols) played on percussion instruments like the tabla or pakhawaj.

Taal, as we know it today, is a mature evolution of this journey. It is no longer just a metric structure, but a living, looping cycle of time. A cycle that can be symmetrical or asymmetrical, steady or playful, slow or blisteringly fast — yet always returning to the same, the first beat, like a pilgrim returning home.

What Makes a Taal? The Structure Unfolded

Taal isn’t merely about counting beats. It’s a multi-layered framework that has depth, dynamics, and grace. Let’s understand the anatomy of a typical taal:

- Matra (मात्रा): The fundamental unit — a beat.

- Vibhag (विभाग): Groupings of beats, often shown through hand gestures.

- Taali (ताली): A clap that marks emphasis.

- Khaali (ख़ाली): A wave of the hand, showing contrast — lightness.

- Sam (सम): The first beat of the cycle — the gravitational centre of music.

For example, in Teentaal, the most popular taal in Hindustani music:

- It has 16 matras, grouped as 4+4+4+4.

- The 1st beat (sam) is clapped.

- The 5th and 13th beats are also clapped (taali).

- The 9th beat is waved (khaali), giving a sense of lift.

Each matra may carry a bol — a mnemonic syllable that indicates the stroke played by the tabla. These bols aren’t just technical markers — they’re poetic, percussive expressions that create texture and dialogue in performance.

What is Theka? Is it the Rhythmic Signature?

While taal is the skeleton, theka is its heartbeat. It’s the actual sequence of bols (like dha, dhin, dhin dha) that a tabla player plays to articulate the structure of the taal. Every taal has its own theka — unique in its swing, mood, and character.

Theka acts as a constant companion to the vocalist or instrumentalist. It helps establish a mood in slow vilambit compositions and provides lift in fast drut renditions.

A master tabla player knows when to be firm, when to be gentle, and when to converse, making theka a deeply sensitive, almost sentient presence on stage.

Taal as Dance: Elegance in Motion

One of the most beautiful metaphors for taal is dance. When a performer improvises (alap or taan), they often stretch or compress phrases, float over beats, and return triumphantly to the sam — much like a graceful dancer spinning around and returning to their starting point.

In fact, Indian classical dance forms like Kathak or Bharatanatyam directly embody this relationship. Dancers use footwork (tatkar), hand gestures (mudras), and spins (chakkars) in precise rhythmic sync with the tabla, exploring the symmetry and asymmetry of taals like Teentaal, Jhaptaal, and Rupak.

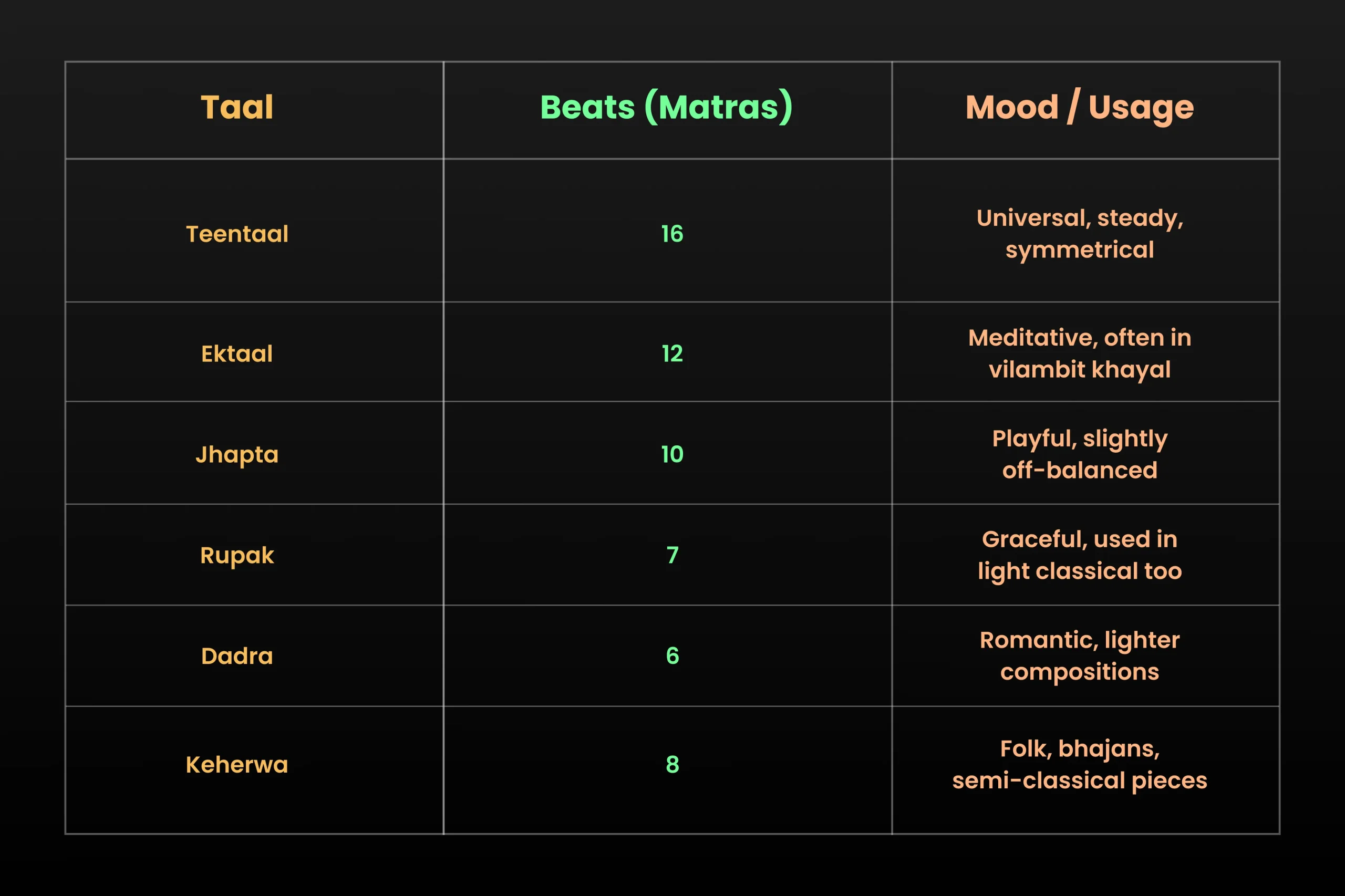

Popular Hindustani Taals and Their Essence

Each taal brings its mood and rasa, and even the same raga feels different when presented in a different rhythmic cycle.

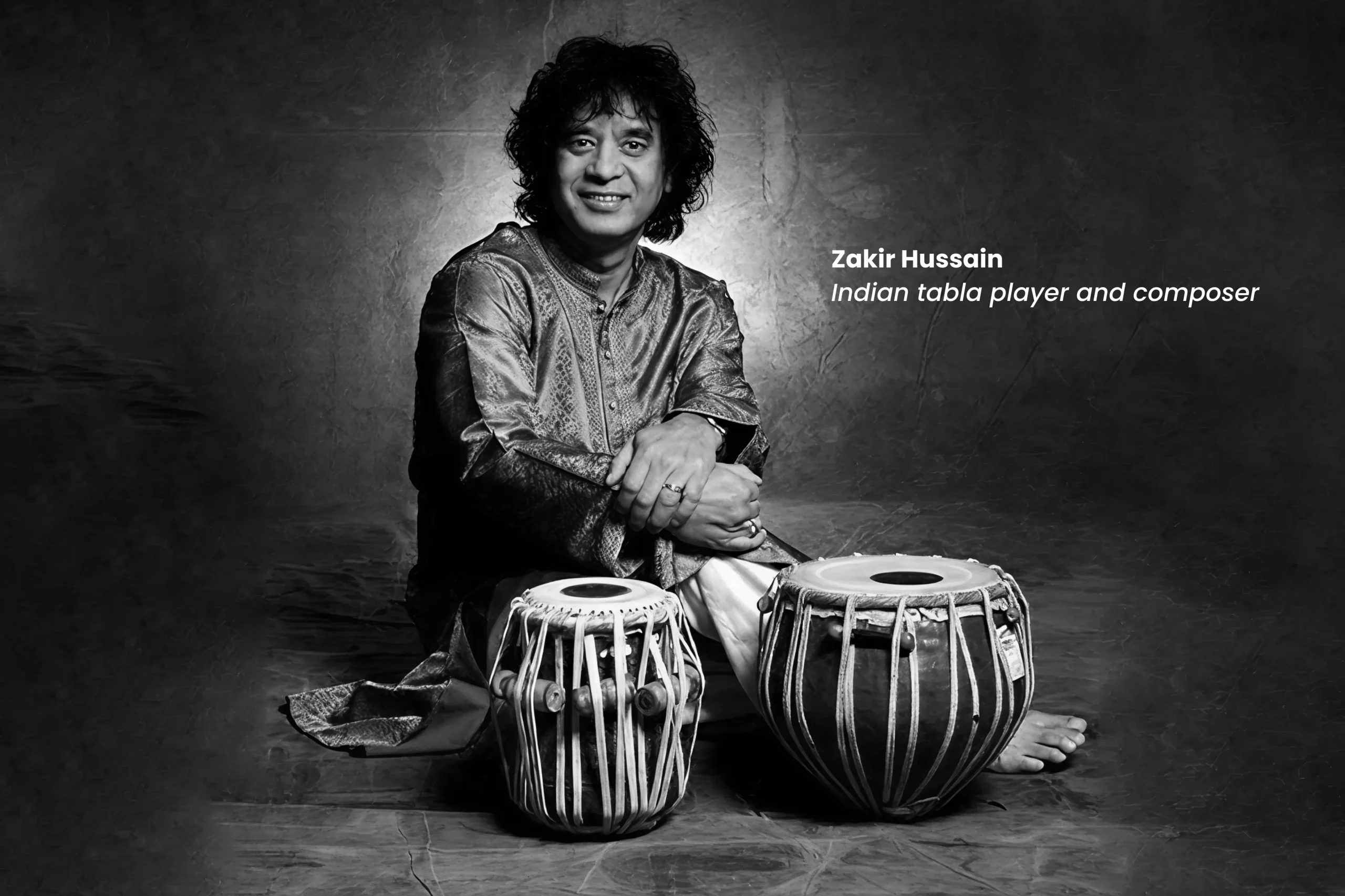

Taal as Language: A Tabla Player’s Universe

For a tabla artist, taal is more than a timekeeper — it is a language. The theka is only the beginning. Within that structure, a tabla player weaves peshkar, kaida, rela, tukra, tihai, and more — each a rhythmic composition that balances creativity with mathematical logic.

The interplay between melody and rhythm becomes a conversation. The vocalist may signal a return to Sam with a glance. The tabla artist may respond with a tihai (a rhythmic phrase repeated thrice) landing on the sam. When done well, this creates goosebumps — not just technical brilliance, but emotional climax.

Taal and Tempo: Laya, Vilambit to Drut

Taal doesn’t exist in isolation. It travels with laya — the speed or tempo. In Hindustani classical music, a single composition may begin in vilambit (slow tempo), transition to madhya (medium tempo), and conclude in drut (fast tempo).

The change in laya transforms the experience:

- Vilambit allows for deep, introspective improvisation.

- Madhya brings a sense of motion.

- Drut is exhilarating, full of dazzling taans and rhythmic fireworks.

In this way, taal is like time itself — it stretches, shrinks, expands, and contracts — but never loses its cycle.

For the Listener: Taal as an Unconscious Experience

Even if you don’t consciously count beats, your body knows. Your foot taps. Your head nods. That’s tala at work in your bones.

Listeners in Indian classical concerts often show appreciation when the Sam is struck perfectly after a long taan or tihai. The joy of returning to Sam is like the feeling of resolution in a story — a return to equilibrium.

Taal and Life: Freedom Within a Framework

What makes taal truly beautiful is the paradox it embodies: structure and freedom. It provides a reliable, steady framework — yet within it, artists soar. They take risks, explore silence, stretch notes, and test the limits of time — but always return to Sam.

This philosophy mirrors life itself. We navigate responsibilities, emotions, dreams, and detours — but always return to our grounding principles. Taal teaches us discipline and release, control and surrender.

The Spirituality of Cycles

In the end, tala is not just rhythm. It is a time made musical. It connects the past and present in a loop — like seasons, like breath, like mantras.

It is a philosophy that teaches us how to move forward… and how to return. From chhand to theka to taal — it’s a story of evolution, devotion, and timelessness.

So the next time you hear a tabla, listen not just with your ears, but with your breath, your pulse, your heart. Because in that rhythm lies something truly eternal.

~~ Written by Kaustubh Bagchi (Ghazal, Hindustani Classical Teacher at Artium Academy)

FAQs on Tala

In Indian Classical Music, both Hindustani and Carnatic traditions use a variety of taals (rhythmic cycles), but in practice, about 15 to 40 are commonly used. Hindustani music features taals like Teentaal, Ektaal, Jhaptaal, Rupak, Dadra, and Keharwa, while Carnatic music is based on 7 main tala families (Suladi Sapta Talas), expanded into 35 types through rhythmic variations, though Adi Tala, Rupaka, Misra Chapu, and a few others are most frequent in concerts.

In Hindustani classical music, raga and tala are two foundational elements, but they serve very different roles. A raga is a melodic framework — it’s a specific arrangement of notes that evokes a particular mood or emotion. It defines what you sing or play. On the other hand, tala is the rhythmic cycle — the time framework that governs when you place each note. While raga gives the music its soul and identity, tala gives it structure and flow, like melody and rhythm dancing together in perfect balance.

The term Teentaal comes from two words: “teen” meaning three and “taal” meaning rhythmic cycle. However, Teentaal does not literally mean “three beats” — instead, it refers to a rhythmic cycle of 16 beats, which is divided into 4 equal parts (vibhags) of 4 beats each. The “teen” in Teentaal is a traditional naming convention, not a count of beats. It is one of the most widely used and versatile taals in Hindustani classical music, especially in Khayal, instrumental music, and dance.

Taal, Chhand, and Theka are interconnected but distinct concepts in Hindustani classical music:

- Taal is the overall rhythmic cycle, a repeating time structure made up of a fixed number of matras (beats). It provides the foundation for rhythm in performance.

- Chhand refers to the metrical pattern or rhythm of the words or syllables, often seen in lyrics, compositions, or tabla phrases. It adds poetic or mathematical structure within or across the taal.

- Theka is the actual pattern of bols (syllables) played on the tabla that expresses the structure of the taal. It acts like the taal’s audible blueprint and helps the listener and performer stay oriented in the cycle.

In simple terms:

🔹 Taal is the time cycle

🔹 Theka is its spoken or played pattern

🔹 Chhand is the poetic or rhythmic design within that cycle

Taal plays a foundational role in classical Indian dance forms like Kathak and Bharatanatyam, acting as the rhythmic framework that shapes the movement, expression, and structure of a performance. In Kathak, the dancer’s intricate footwork, spins, and gestures are tightly interwoven with the lay (tempo) and theka (rhythmic pattern) of the chosen taal, often interacting in real-time with the tabla or pakhawaj player in a kind of rhythmic dialogue. In Bharatanatyam, the nattuvanar (conductor) recites rhythmic syllables (solkattu) in sync with the mridangam and the dancer’s movements, which are choreographed to align precisely with the beats and accents of the tala.

Ultimately, taal transforms the dance into a visual expression of rhythm, where every gesture, step, or pause becomes a response to the underlying rhythmic cycle — making it not just music in motion, but rhythm brought to life.

Taal is considered spiritual or philosophical in Indian classical music because it embodies more than just rhythm — it reflects the cyclical nature of time, life, and the universe. Unlike linear Western timekeeping, taal moves in loops — beginning, flowing, pausing, and returning — mirroring the eternal cycles of creation, preservation, and dissolution found in Indian philosophy. Each return to sam (the first beat) symbolizes a homecoming, a reset, much like the soul’s journey back to its source.

In a spiritual sense, surrendering to the discipline of taal teaches the musician humility, patience, and presence. It becomes a meditative framework, where the artist transcends ego and merges with the pulse of the cosmos. Taal, then, is not just time measured — it’s time felt, lived, and ultimately, revered.